Read more about American History

There’s a surprisingly long list of US presidents who died in office. Today, the most famous to have been assassinated are Abraham Lincoln and John F Kennedy.

The stories of their deaths are so firmly imprinted in the public consciousness that even the killers’ names are instantly recognisable. However, while you might know about John Wilkes Booth and Lee Harvey Oswald, the name Charles Guiteau is more likely to draw a blank stare.

Netflix is looking to change that with the new drama series Death by Lightning. It adapts the oft-overlooked tale of Charles Guiteau, the religious fanatic who shot US president James Garfield in 1881. What else do we at Sky HISTORY know about the would-be assassin?

Charles Julius Guiteau was born on 8th September 1841 in Illinois. Guiteau’s mother Jane died in 1841, leaving his father, Luther, to raise him from then on.

Luther is known to have been a man of religious fervour who physically abused his son. There are many intriguing what-ifs about Guiteau - one of them being what his upbringing would have been like if his mother had not died prematurely.

In this alternate timeline, could Jane have potentially reined in her husband’s brutal parenting methods? Could this, in turn, have prevented the religious mania and dangerous self-delusion that would come to characterise Guiteau as an adult?

In 1960, Guiteau joined a New York-based religious sect called the Oneida Community. The group practised ‘free love’, where all male members were considered married to all female members.

Despite this, women there repeatedly rejected Guiteau’s sexual advances. He even picked up the unflattering nickname ‘Charles Gitout’. He ultimately left the community, but subsequently made a failed attempt to launch a newspaper promoting the Oneida faith.

Guiteau later tried his hand at bill collecting. In this endeavour, he is said to have kept a disproportionate share of the collected money for himself.

By the 1870s, Guiteau had turned his attention to the political world, hoping it would give him the career breakthrough he had long sought. As the 1872 presidential election approached, he delivered a speech supporting the Democratic candidate Horace Greely.

Though Greely was heavily defeated at the ballot box, Guiteau remained convinced that God was guiding him on a divine mission. This attitude did not please Guiteau’s father, who believed his son to be not merely insane but – worse – possessed by the devil.

By 1880, Guiteau had switched his political allegiance to the Republican Party. At that time, the ‘spoils system’ still reigned supreme in US presidential politics. This was the expectation that the president would fill political posts with loyalists, rather than people deemed the most competent for the job.

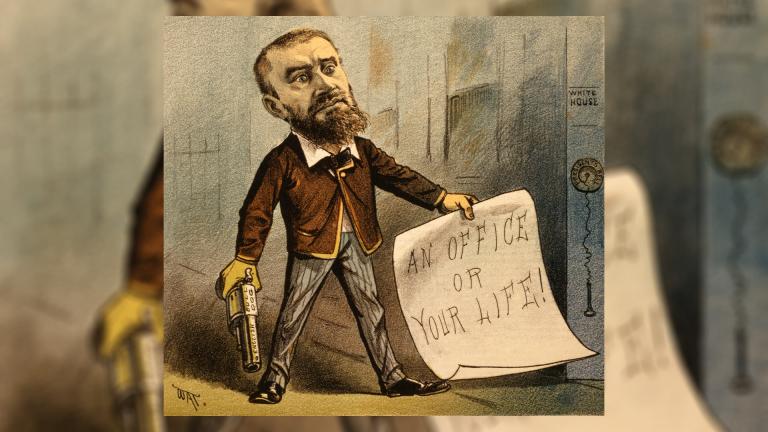

So, after James Garfield became the Republican candidate for that year’s presidential election, Guiteau waxed lyrical about Garfield. Guiteau hoped that, as a result, the latter would not only win the election but also hand him a political position soon afterwards.

While the first part did happen, the second failed to materialise despite Guiteau’s repeated pleas to the new Secretary of State, James Blaine. Guiteau also feared that Garfield was about to do away with the patronage system.

Guiteau believed that, by assassinating Garfield, he could put Vice President Chester A Arthur in the White House. In return, Guiteau thought, the new president would reward him with a role in his administration.

At a Washington railway station on 2nd July, Guiteau snuck up on Garfield and, with a British Bull Dog revolver, shot him in the back. Though Garfield received medical treatment for the resultant wound, he contracted an infection that eventually claimed his life on 19th September 1881.

Guiteau was subsequently put on trial, accused of the late president’s murder. Guiteau insisted that God had taken away his free will and authorised him to assassinate Garfield, despite the Biblical commandment that ‘Thou shalt not kill’.

This excuse did not wash with jurors, who found him guilty of murder - a charge carrying a death sentence. At the gallows on 30th June 1882, Guiteau was permitted to read out a self-penned religious poem, ‘I Am Going to the Lordy’.

After Guiteau’s hanging, the US presidency finally abolished the spoils system, replacing it with a much more meritocratic approach.

Keen to deepen your knowledge of US presidential history? You can do exactly that by signing up to the Sky HISTORY newsletter.