Richard Arkwright: Biography

‘Cotton King’ Richard Arkwright was the father of the factory; the ‘Ford’ of his day; and one of the founders of the industrial revolution.

“The spinning wheel made England into a powerhouse.”

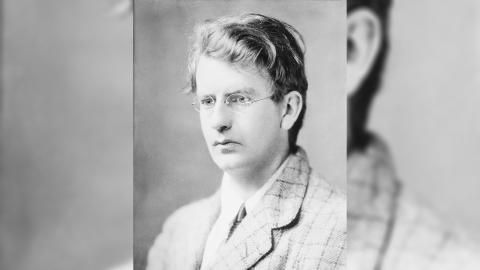

Mark Frauenfelder

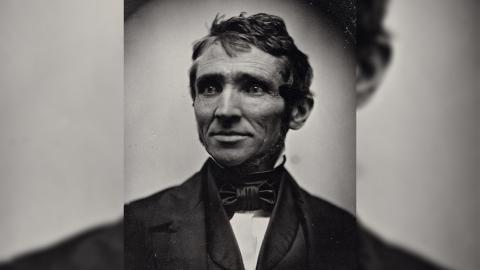

Richard Arkwright is born in Preston on 23 December 1732. He’s the youngest of thirteen children. Only seven of them make it through childhood. His father, Thomas, is a struggling tailor. Richard will have a lifelong fascination with fabrics and attraction to wealth. The last of a large family, there’s no money to school him. So his cousin Ellen teaches him to read and write. Richard determines to escape the poverty of his situation.

He starts works as an apprentice barber. In 1755, he marries Patience Holt. They have a son. But a year later, Patience is dead. Grief gives way to ambition. Richard, a hairdresser, decides he wants to become an entrepreneur and start his own company. Richard’s second marriage is to Margaret Biggins in 1761. They have three children. Only their daughter survives into adulthood.

WATERPROOF WIGS

Arkwright believes the real money in hair is not in cutting it, but in collecting it. He decides to manufacture male wigs. But by the time he starts up his own Bolton based business in 1762, the fashion for them is already passing its peak. During his travels round the country collecting hair he comes across a method for dyeing it that makes it waterproof. The extra cash it generates will give him the money to finance the development of his first spinning machine. But it’s his ability to network on his travels, with weavers, spinners, indeed anyone with a better idea than him that will really make his fortune.

COTTAGE INDUSTRY

When the wig making business starts to decline, Arkwright explores the new mechanical inventions in the textiles industry. The textile business at this time is often literally a cottage industry. Raw cotton is turned into threads using a spinning wheel in the family home. These turn cotton or wool into threads, one at a time, which are then woven onto looms to make fabric. This fabric can be then used to make, for example, clothes. It’s an extremely laborious process. There’s a technological race to find a mechanical solution. Arkwright believes he can make his fortune from the right invention.

MAN TO MACHINE

A machine for carding cotton, forming strands of cotton ready for spinning, and a labour saving spinning jenny has already been invented by the time Arkwright enters the race. In 1767, he teams up with a Warrington watch and clockmaker, John Kay. Kay and reed-maker Thomas Highs have been working on a mechanical spinning machine. But a lack of funding frustrates them. With Arkwright’s financial backing, Kay creates a working machine. It substitutes the need for human hands and fingers using instead machine and metal to create stronger spun thread, more quickly and easily. It will revolutionise the world of work but it will also make thousands of skilled workers obsolete.

Their first spinning frame is put into use in 1768. Able to spin 128 threads at a time, it’s faster than anything before it and the thread it produces is stronger.

It is the first powered, automatic, and continuous textile machine.

It marks the move away from home production to mass manufacturing in factories.

“Arkwright didn’t just invent the spinning machine. He invented the modern factory.”

Edward Meig

In 1769, it’s Arkwright who needs finance to expand. And it’s his banker who introduces him to Jedediah Strutt, the modifier of the stocking frame (essentially a knitting machine) and businessman Samuel Need. Strutt and Need are impressed with Arkwright's machine and agree to form a partnership. Arkwright’s machines will convert the raw cotton and then Strutt and Need will use the thread in their knitting business. That year, Arkwright takes out a patent on his spinning machine.

THE FIRST FACTORY?

As Arkwright's spinning frame is too large to be hand operated, horses are employed. But when this experiment fails, they harness the power of the water wheel.

In 1771 the three men set up a large water powered mill factory on the banks of the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright's machine now became known as the Water-Frame. It is the world’s first successful water powered cotton powered spinning wheel. But the water supply at Cromford proves erratic.

Copying the methods of the existing silk mills, Arkwright brings together workers into one specialised workplace. And as there aren’t enough local people to supply Arkwright with the staff needed, he builds a large number of cottages close to the factory. And then he moves people in from all over Derbyshire. Arkwright prefers weavers with large families so that women and, especially their children, can work in the spinning-factory.

He also opens up a mill in Chorley and by 1774 is employing 600 people there. And just as the cotton factory system rapidly taking shape, the government removes the costly import tariff on raw cotton. A small group of men are about to become very, very rich.

In 1775, Arkwright makes various modifications to a Lewis Paul carding machine improving its ability to disentangle, clean and intermix fibres. He patents his ‘invention’ that year.

Arkwright's fortunes continue to rise. He’s mechanised the preparatory and spinning process. He now develops mills in which the whole process of yarn manufacture is carried on by one machine. Productivity increases are further complemented by a system in which labour is divided, greatly improving efficiency and increasing profits.

Arkwright is the first to use James Watt's steam engine to power textile machinery, though he only used it to pump water to the millrace of a waterwheel. From the combined use of the steam engine and the machinery, the power loom is eventually developed.

From 1775 a series of court cases challenge Arkwright's patents as copies of others work. If he’s concerned, he doesn’t show it. He purchases a large estate and begins building a castle to be his home.

RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE

In 1779, arsonists destroy his new Chorley mill. Arkwright’s machines make skilled workers jobless and employ only cheap unskilled labour, often children, instead. Apart from an engineer to repair the machine, everyone else is expendable.

The anti-technology, machine destroying Luddites are yet to emerge. But their grievances are first aired around Arkwright.

In 1780 Ralph Mather publishes a book detailing Arkwright’s new factory system:

"Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more."

Richard Arkwright's employees work 13 hour days from 6am to 7pm and he employs children as young as six years old. In some factories, two-thirds of Arkwright's staff are children. He avoids employing those over forty and workers need to have their wits about them. In one factory, there is a machine called ‘The Devil’. It opens and breaks up raw bales of cotton using large rotating spikes. Accidents, mainly amputations, are common. And like most industrial factories, fatalities occur.

But despite being no Cadbury, for his time, he is a considerate boss. And many of his workers stand ready to defend him against the machine breakers. Despite this, the incredible profits possible mean industrial espionage is rife. Workers sell secrets away. Others start building their own water-powered textile factories.

COTTON KING

When Strutt’s old business partner Samuel Need dies in 1781, Strutt dissolves his partnership with Arkwright. He fears Arkwright is expanding too far and too fast.

Before he’s finished, Arkwright will have built mills in Manchester and all the way from Staffordshire to Scotland.

In 1783, Arkwright builds the showpiece cotton mill Masson Mills at Matlock Bath, Derbyshire. A single water wheel harnesses the river delivering ten times the power of Cromford. This six storey expensive red brick design denotes wealth.

But these riches attract many who dispute Arkwright’s patents.

SUITS YOU SIR

Arkwright’s business habit of borrowing others ideas, especially reed manufacturer Thomas High’s, leads to lawsuits. Arkwright is no stranger to court having tried unsuccessfully to protect his patents before. This time, the court hears from Highs, Kay, and Kay’s wife. They are not the only ones to testify that Arkwright has stolen their ideas. But the case is not just about Highs and Kay being recognised and receiving reparations. Many are using Arkwright’s patented creations and don’t want to pay him royalties. In 1785, his patents are revoked.

But by then, Arkwright has made his money. Through leasing, shares and financing, he has interests in over a hundred factories. The following year, he’s knighted.

When he dies, on 3 August 1792, estimates put Sir Richard Arkwright’s personal fortune at half a million pounds, over £200 million in today’s money.

FATHER OF THE FACTORY SYSTEM

Arkwright was born into poverty. Through his entrepreneurship, he could afford to build a castle as a family residence. Many dispute how much Arkwright actually invented, borrowed or stole from others. But most agree his cotton spinning empire helped kick-start the industrial revolution. And for his innovative approach to production - grouping together a workforce in large buildings housing powered machinery - the Victorians will dub him the ‘Father of the factory system’.