Read more about Science and Technology

It’s easy to reel off a list of famous inventors whose inventions had lasting impacts on the world as we know it. Just think of Thomas Edison’s work on the electric lightbulb and Alexander Graham Bell for giving us the telephone, for a start. Also, what would our summer holidays be like today if it weren’t for the Wright brothers’ advances in aviation technology?

Nonetheless, not all inventors have achieved the levels of fame they really deserve. We at Sky HISTORY have dug deep in the archives to uncover the following examples whose names were almost lost in the mists of time.

In the early 19th century, there was a craze for rubber, a material sourced as a milky sap from tropical trees. Rubber was malleable enough to be moulded into many different forms. Keeping it in those forms, however, was a very different matter.

The rubber was found to melt when hot and crack when cold. Even in temperatures that were optimal, it tended to stick to anything it touched. All of this meant that, by the 1830s, the once-thriving rubber industry was on the verge of collapse.

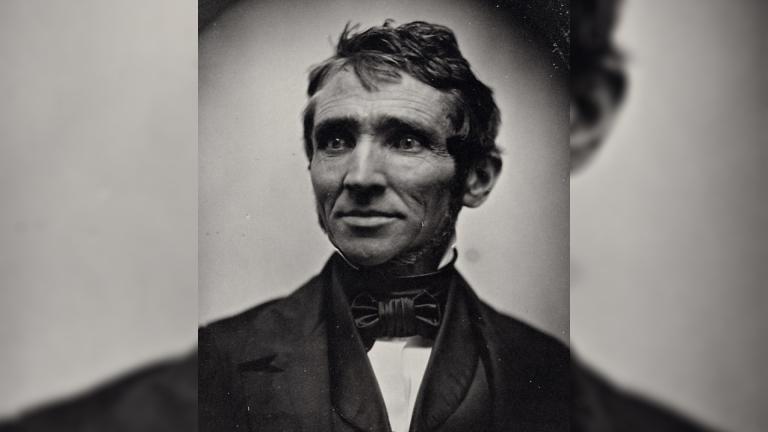

Charles Goodyear was determined to eradicate these drawbacks of rubber. Through a long process of trial and error, he mixed rubber with many different materials. He found that adding nitric acid and sulphur to rubber made it smoother and strengthened its resilience against temperature changes.

However, the real breakthrough happened when Goodyear accidentally dropped sulphur-treated rubber on a hot stove. To his surprise, the rubber hardened rather than melted. This process of making rubber tougher became known as ‘vulcanisation’.

This discovery essentially saved the rubber industry, making the material much more practical to use in a wide range of applications. Goodyear passed away in 1860, several decades before the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company was named in his honour.

Hard though it might be to believe today, windscreen wipers weren’t standard features in the earliest electric vehicles. So, what would drivers do when rain and snow started accumulating heavily on their windscreens, dangerously obscuring their view of what lay ahead?

Usually, the driver would just stop the vehicle from time to time and manually remove the windscreen moisture with their hands. However, Mary Anderson imagined a windscreen wiper blade the driver would be able to operate without leaving the vehicle.

Though she got the device patented in 1903, this was well before automobiles became ubiquitous. So, by the 1910s, when windscreen wipers were commonplace on cars, Anderson’s contribution to the idea had been largely forgotten.

Next time you put some food in a microwave oven, spare a thought for Percy Spencer, who invented it. Yes, the microwave oven, not the food — though it was reportedly a mishap with food that initially gave him the idea for his culinary invention.

The oft-told story goes that Spencer was building magnetrons when he looked in his pocket and noticed that a chocolate bar there had melted. According to his grandson George 'Rod' Spencer Jr, it was actually a peanut cluster bar. Percy later realised that microwaves emitted by a nearby magnetron had brought about the melting.

When the earliest commercially produced microwave oven was released in the 1940s, it was an undoubtedly unwieldy affair. It measured about six feet tall and weighed roughly 750 pounds. Foodies had to wait another two decades before microwave ovens on the market began to resemble those we know today.

Strictly speaking, Hedy Lamarr is far from forgotten. In fact, she was a star of Old Hollywood. Many of her best-known films - including Algiers (1938), Boom Town (1940) and Samson and Delilah (1949) - can still be watched online today.

Nonetheless, as you download these films over Wi-Fi, you might not realise how Lamarr had a hand in the emergence of this wireless technology. Lamarr was passionate about not only acting but also inventing.

During World War II, Lamarr recognised how navies could ensure torpedoes they fired would remain on target. The idea was to control the torpedoes remotely via radio waves, but use ‘frequency hopping’ to prevent these signals from being intercepted by the enemy.

Though Lamarr secured a patent for this idea, it was considered too far ahead of its time. For this reason, it was not actually used during the war. Instead, it eventually helped other inventors to develop various (now widely adopted) wireless communication standards - including GPS, Bluetooth and, yes, Wi-Fi.

For further insights into unjustly overlooked developments that actually changed the world, subscribe to the Sky HISTORY Newsletter.