'Secrets of the Lost Liners': Stephen Payne on designing the Queen Mary 2

'My aim was to produce a ship that would invoke the spirit of the ships of state but be for everybody' Stephen Payne tells Sky HISTORY.

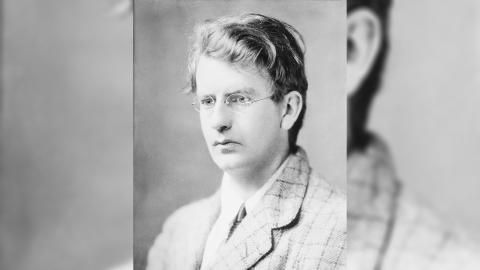

Stephen Payne OBE, lead designer of the Queen Mary 2 | Image: Stephen Payne/Secrets of Lost Liners

Secrets of the Lost Liners dives deep into the history of ocean liners, tracing their design, service, and – in these cases - demise. Beyond exploring the intricacies of liner design and complexity, this exclusive UK series uncovers dramatic onboard events: hijackings, political intrigue, and negligence. Featuring exclusive footage, expert insights, and emotional survivor testimonies, the new series provides a minute-by-minute analysis of each catastrophe, shedding light not only on the greatness and flaws of these ships, but also on the human stories behind their construction, voyages, and tragedies.

The series covers Achille Lauro, Titanic, Empress Of Britain, Oceanos, Costa Concordia and Île de France. To find out more about the series, Sky HISTORY spoke with series contributor, Stephen Payne OBE who was the lead designer of the Queen Mary 2, the only serving ocean liner still in existence.

How did it feel being the lead designer for the Queen Mary 2?

It was a big responsibility. By a strange coincidence, I was sailing on board QE2 when the announcement was made that Cunard had been sold to Carnival Corporation. It was during that trip I was told that there would be a study to evaluate the possibility of building a new transatlantic liner [Queen Mary 2] and as soon as I got back to Southampton, that I was to lead that study. I was only 38.

It was awesome; it was something I had in mind from an early age. So, to be the right person, at the right time was incredible. For a naval architect interested in passenger ships, there couldn't be a bigger assignment to be given

What challenges are there with designing an ocean liner vs a cruise ship?

There is a huge difference. The liner is designed to go from A to B on a set schedule. Whatever the weather, the ship is designed to maintain that schedule.

On a cruise ship if the weather is bad, you can miss a port of call or go somewhere else. With the transatlantic liner, you've potentially got the worst weather in the world on the North Atlantic, even in summer, but you still have to maintain the schedule.

To achieve that, the ship needs to be built much more like an arrow, very fine at the front. Structurally it must be a lot stronger than a cruise ship. It needs more power to maintain the speed in rough weather.

Invariably there's also a lot of fog in the North Atlantic , so you've got to have numerous public rooms inside the ship to keep everybody amused. And all the extra power, strength, public rooms and shape add up to about a 40% increase in the price of building the ship and the cost of operating it.

Getting around this double whammy of the 40% extra in the price of the ship and the operating cost. That was the big challenge.

Image: 'Secrets of the Lost Liners'

The Queen Mary 1 is now retired and used as a hotel in California. Did you base elements of the Queen Mary 2 off the original ship or previous fleets from Cunard?

I've been on Queen Mary twice in California and stayed on the ship for a few nights on each occasion. I must admit there wasn't much from the design of the ship that could be carried over to Queen Mary 2. The only part is the shape of the front of the superstructure, which is stepped down.

I tried to recreate that on the Queen Mary 2, the forward face of the superstructure below the bridge. The black lines at the front of the Queen Mary 2 represent the walkways that were on the original Queen Mary.

I made a big point during the design and building of the Queen Mary 2 that I didn't want anything false on the ship, like fake funnels and things like that. But I did include those black lines and they're the only sort of faux part just to break up that whole white front.

How would you like people to feel after sailing on the Queen Mary 2?

The whole ethos of Queen Mary 2 was that she's a transatlantic liner. I was trying to emulate what we call the ships of state of the 1930s like the Normandie, the first Queen Mary and Nieuw Amsterdam which were grand glamorous ships.

But people look at them with rose-tinted glasses because the people who experienced all that grandeur were just the first-class passengers. First class was invariably only a small proportion of the complete passenger load

The Normandie, for instance, had this fabulous first-class area, whereas the third class was so poor that very few third-class passengers would go on the ship. That's why the Queen Mary was so successful because her third class was a lot better.

My aim was to produce a ship that would invoke the spirit of the ships of state but be for everybody. That's why if you buy the cheapest cabin on board, you get to eat in the Britannia restaurant. I defy anybody to say that isn't one of the most elegant places to eat.

I want people to leave the ship obviously to have had a marvellous experience and to feel “that's the way it used to be” and that we're reliving history. Rewriting history is a phrase I use a lot. Especially to encourage young people to have and realise ambition. The team I worked with effectively rewrote history because everybody said the transatlantic liners would finish when the Queen Elizabeth 2 was retired. With QM2, this is not now the case.

Britain’s history, both royally and politically, is heavily tied with maritime success and adventure. Do you think that highlighting maritime prowess is important to Britain?

Very much so. We're an island nation and there's such a lot of our history that centres around the maritime part. The only reason we weren't invaded in the Second World War is because there's a moat all around us. The old Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary ships helped shorten the war by a year by being able to transport so many troops to Europe.

Which of the liners covered in season two interested you most and why?

The Empress of Britain. She is a largely forgotten Canadian Pacific ship. She used to sail from Southampton across to Canada. She was a large ship, the size of the Canberra and the Titanic. Sadly, she was lost in the war after only nine years of service. But she had this double life where she was a transatlantic liner and an off-season cruise ship.

In the winter months when transatlantic demand was extremely low, they took two propellers off and sailed the ship as a twin-screw ship on a world cruise.

That's an amazing concept to put the ship into dry dock and take two propellers off. The reason being that by operating it with only half the power you’re obviously not spending so much on fuel and it's much more economical.

It’s sad that she’s not more well-known because she had some spectacular interiors, a full-size tennis court on the upper deck and the like.

The Titanic still captures the public’s imagination 102 years on. Why do you think that is?

At the time in 1912 when she left Southampton, there was no real interest because she was the second of the three Olympic class ocean-liners: the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic. It was only when she sank a couple of days later that suddenly there was extra interest.

You’ve got to imagine here that she’s the largest passenger ship and the largest moving object made by man, sinking on her very first trip. Then you’ve got all the social story of all the multimillionaires with Bruce Ismay, the owner, jumping into a lifeboat. You’ve got all the makings of a tremendous story there.

There are big discoveries all the time. Since the wreck was discovered, we’re finding out new things about how the ship sank.

Titanic is crucial to everything we do today at sea, because all the maritime regulations, which we call SOLAS 'the safety of life at sea', stem directly from the Titanic disaster. Immediately after the ship sank, the maritime nations of the world got together to form this maritime convention of rules.

Watch Stephen share his expert knowledge of these wonders of the sea in Secrets of the Lost Liners. Brand new and exclusive on Mondays from 29th April at 10pm.