The World Health Organisation has recently released a plan designed to meet ‘the greatest threat to global public health.’ The report describes the threat as neither predictable nor preventable, and not a question of if it will strike the world, but when. The Global Influenza Strategy 2019-2030 aims to enable the world to better coordinate and respond to the threat posed by a potential influenza pandemic. In our increasingly globalised and interconnected world the threats posed by such pandemics are taken extremely seriously. This is due, in part, to the experiences of a previous pandemic, when global movements saw a virus emerge that would devastate a worldwide population already scarred by the carnage of war.

Although a number of pandemics have occurred in previous decades, the most deadly was the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919. The Spanish Flu has been described by the author Laura Spinney as ‘the greatest tidal wave of death since the Black Death, perhaps in the whole of human history.’ This pandemic is estimated to have caused the deaths of between 50-100 million people and infected one-third of the human population, around 500 million people. The flu killed far more than either the First or Second World Wars, and may even have killed more than the death tolls from both conflicts combined. The flu forced fundamental changes to public heath care systems across the globe and its severity and impact is still felt today.

The flu that most people are aware of is a seasonal virus that circulates across the globe in the colder months. Although the flu virus can effect humans, it is also prevalent in birds and mammals. Sometime in late 1917 or early 1918 a strain of avian flu managed to make the transition from birds to humans. Historians still debate the exact location of ‘patient zero,’ the very first human to become infected with this deadly new strain. Some scientists such as British virologist Professor John Oxford argue that the outbreak began in a hospital camp in Etaples, France, whilst others suggest that it began in a US Army camp in Kansas.

Spain was immune from the censorship that limited the wartime nations press. When the Spanish King was struck down many newspapers were finally able to report on the outbreak that was sweeping across the world. These press reports then led to a mistaken belief that the outbreak had started in Spain.

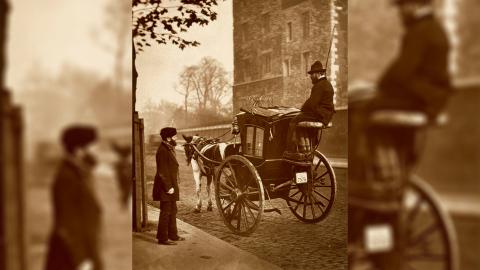

The unusual circumstances of 1918 helped the virus to travel further and faster than in any previous event in human history. The First World War resulted in the largest global migration of humans yet seen. This enabled the virus to spread, on troopships and transports, to every corner of the globe. Furthermore, the large concentrations of people, especially in the military, enabled the virus to infect individuals with lightning speed.

Although the study of bacteria was well known, the presence of viruses had been postulated but never proven because no equipment then existed to observe something so small. This meant that when the outbreak occurred there was no way of studying the virus effectively or developing a cure.

The Spanish Flu instead appeared to target young men and women between the ages of 18-35

A further terrifying feature of the outbreak that was apparent from its onset was the main age group of its victims. Seasonal influenza normally targets children under the age of 4 or elderly grandparents over the age of 65. The Spanish Flu instead appeared to target young men and women between the ages of 18-35. This age group normally has the strongest and healthiest immune systems, able to fight off any illnesses. However the Spanish Flu turned its victims own immune systems against them. The virus would trigger a Cytokine Storm, an autoimmune response whereby the victims immune system goes into overdrive, attacking and causing significant damage to lung tissue. This damage would cause the victims to turn blue as their bodies battled for oxygen. Victims would then eventually drown as their lungs filled with fluid.

The first wave of the outbreak in early 1918 was mild by comparison, but by August a second far deadlier strain was sweeping the world.

The devastating impact of the virus is illustrated in the ways it affected local communities. The first reports of the virus hitting the town of Crewe in the North West of England occurs in June of 1918. It reportedly laid low many of its residents, especially in its large railway works which would prove the perfect breeding ground for the virus. By November the virus had claimed 60 lives in just a 10 day period and resulted in 115 internments in Crewe’s cemetery, the highest in any month since the cemetery opened. In November 1918 of the 38 men killed on active service 18 are confirmed to have died of an influenza related illness.

The influenza virus is a parasite that can only live in an infected host. The most successful strain would be the one in which the host stayed alive, enabling the virus to be passed on. If the virus killed the host its chances of being passed on become limited. This helps to explain the spikes in death rates, and why the virus came and went so quickly. The virus became a victim of its own success, its deadly nature resulted in victims failing to pass on more deadly strains, which eventually led to the virus appearing to seemingly vanish after the end of the third wave in 1919.

The virus caused worldwide devastation to communities ravaged by the effects of war. The world of 1920 wanted to forget the terrible experiences of the war years, and so the Spanish Flu was confined to memory. In the years that have followed however, scientists have studied its devastating effects, using the outbreak as a model in how to cope with future pandemics. The virus is still around today, although in a less deadly form than when ‘the Spanish Lady’ first struck one hundred years ago.